A Dip into Machine Learning Applications in Particle Physics

Published:

As part of the Metis data science boot camp, we were required to investigate a topic and then present on it. With my background in particle physics, it’s no surprise that I was interested in learning about related machine learning applications. Since I never did any machine learning work as part of my graduate degree, I thought I would take advantage of the opportunity.

Please note that I am not an expert in this subject. Most of the material I will go through here has come from a lot of online searches. At the end of this post is included a list of sources I found very educational, which I took inspiration from. If you spot any misrepresentations in the material below, please do not hesitate to reach out to me so that I can correct them.

What is particle physics and why use machine learning?

Particle physics is the study of the basic blocks of matter, and the interactions between them. The majority of research is driven by large accelerators and particle colliders. These accelerators crash particles into each other, or into some material, in order to produce new interesting particles and interactions. By measuring what happens after these particle collisions with various experiments, physicists can derive the underlying laws which govern our universe. Up to a billion collisions happen a second as these accelerators run, and the experiments gather an astronomical amount of data every second, leading to some of the largest datasets in the world. And as anyone in the data science and machine learning world knows, a wealth of data is exactly where machine learning becomes really useful.

|

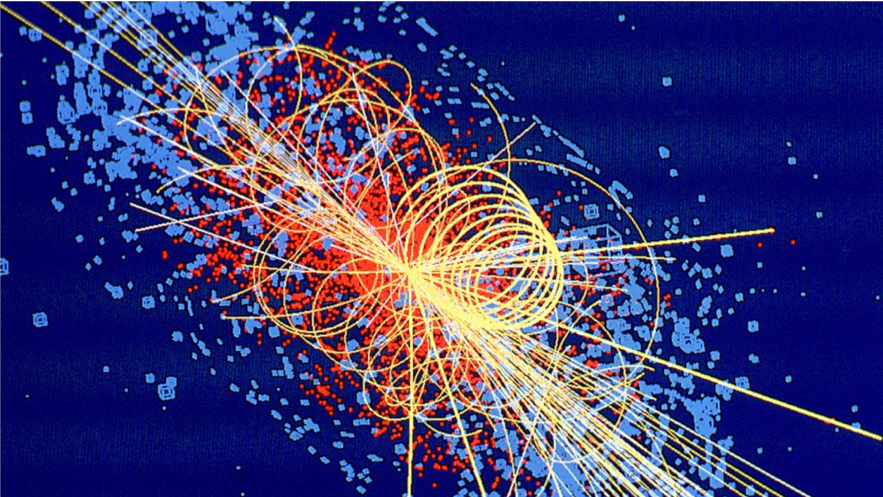

|---|

| Beamline tunnel at CERN in France and Switzerland. |

In general my feeling for the physics community is that there is somewhat of a split in attitudes as to the acceptance of machine learning methods. Some people are against it in favor of the more traditional “physics-based” modeling, and argue against the black-box nature of many machine learning models. Others are for it and have put it to good use. There’s certainly no denying it’s effectiveness in some very key areas. As more and more research is done into the subject, and the community-wide understanding of machine learning methods grows, it will make it’s way into more and more applications.

Most of the active research has been done in the last few years, with some of the earliest examples going back ten years or so. Supervised learning models are primarily used, which is unsurprising to me as supervised learning is where every industry and application starts before moving on to unsupervised techniques. (It also aligns more directly with the hard-science nature of physics.) As for the techniques themselves, most of the earlier models were along the lines of decision tree ensembles, with one result of note being that of the discovery and measurement of the Higgs boson in 2012, using boosted decision trees. Nowadays however, most of the recent models are some type of neural network or other.

Applications

I’ll go through a few use cases now, keep in mind that this list is by no means exhaustive.

Triggering and event selection via classification

If the experiments mentioned up above gathered all data that was produced, the data rate would be of order peta-bytes of data per second. (That’s a lot!) In order to reduce this to a manageable level, giga-bytes per second (still a lot), the data is filtered with various trigger systems which decide whether an event was important enough to keep. Most experiment trigger systems currently use traditional, hard-cut, techniques. Some, like the CERN LHCb experiment however, use machine learning classification methods, and more are planning on doing so. The power and flexibility of these new methods open up new opportunities for improved data taking and selection. As any good scientist knows, getting the useful data is often the hardest part. By improving the data pipeline at the very beginning, every later stage is improved. With the LHC experiment ramping up this decade to it’s high-luminosity phase, the data rate is only going to increase, and machine learning techniques will play a pivotal role.

|

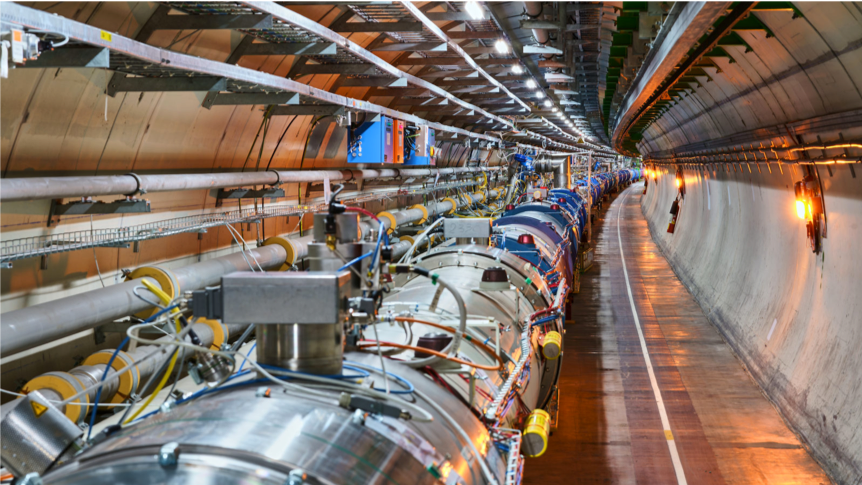

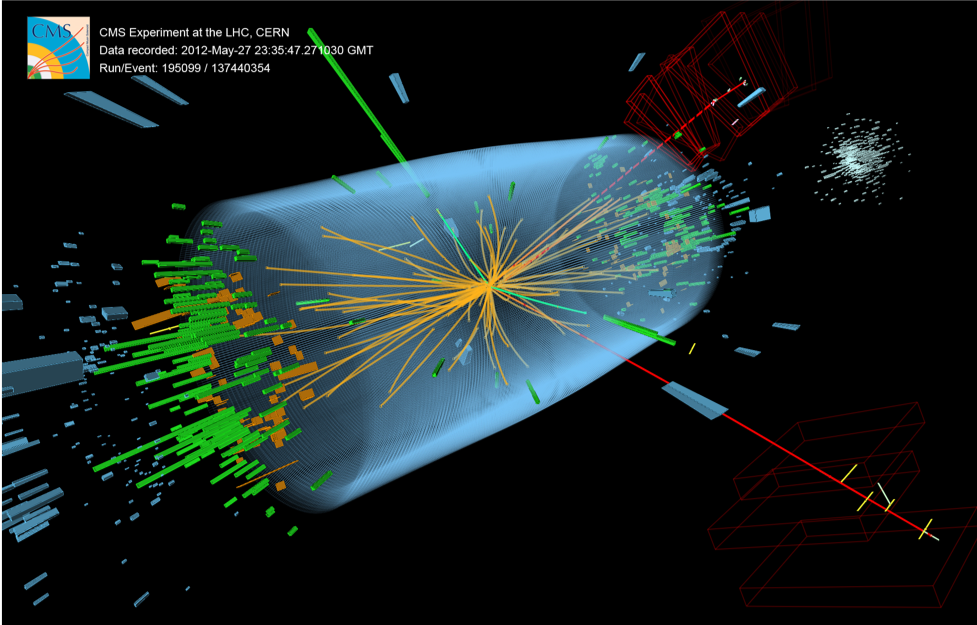

|---|

| Event display of a collision at the CMS experiment at CERN. |

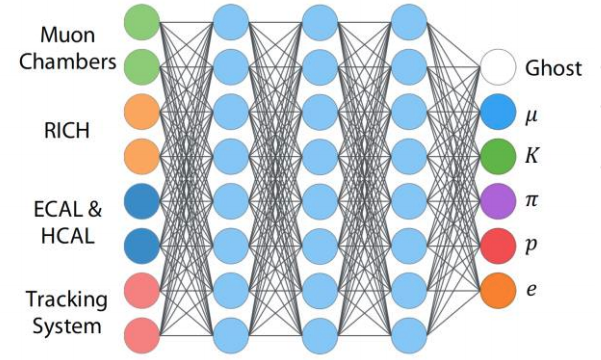

Particle and jet identification via classification

Beyond event selection, machine learning classification methods can be used for particle identification. Detectors record a wealth of information as particles pass through them, and that information corresponds to particular signatures which can be used to identify and separate them. As a more complex use case, classification algorithms can be applied to so-called jets. A jet is a shower of particles all originating from a single parent particle. As that parent particle passes through materials it will produce other particles, each of which will then produce it’s own daughters, and so on until all the energy is exhausted. The constituents of the jet and it’s overall behavior will be dependent on the origin particle. The combination of the individual particle signatures can be used to classify the origin. Beyond that, jet profiles (2D histograms) for different sources can be recognized with image recognition techniques using convolutional neural networks. Additionally, recurrent or recursive neural networks offer some interesting possibilities for identifying whether specific particles are part of a jet or not. Machine learning methods have been put to good use in these areas, and there is a lot of on-going research.

|

|---|

| Example architecture of a particle identification neural network at LHCb. Source |

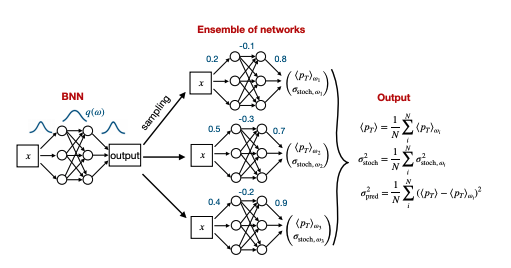

Particle and event parameter estimation via regression

Of course, there are are many use cases for regression methods in particle physics. Parameters for particle measurements need to be evaluated either for the final analysis results or in the steps leading up to it. Classical regression methods have long been used to great success, but machine learning methods may offer new insights or power where this parameter estimation is difficult. One paper I ran across was from a group of researchers utilizing Bayesian neural networks to estimate simulated jet momenta and the associated statistical and systematic uncertainties. This last mention deserves a bit more explanation, in that knowing the uncertainty on a measurement is just as important as the measurement itself, for without the former the latter is meaningless. Understanding how to determine measurement uncertainties dependent on the machine learning methods themselves is an active area of research. As this understanding grows and the black-box nature of these algorithms becomes less and less opaque, machine learning methods will only become more utilized.

|

|---|

| Example architecture for a Bayesian neural network which extracts a particle’s momentum and the associated error on it. Source |

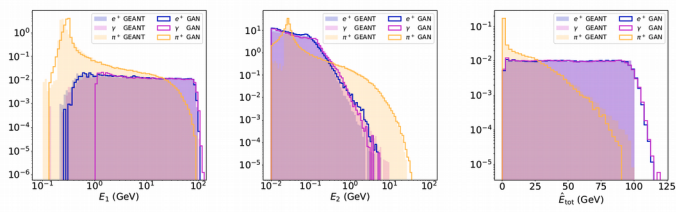

Faster simulation via GANs

As a last use case example, GANs (generative adversarial networks), can be used for faster simulation of particle distributions. A wide variety of particle distributions are constantly simulated as part of an experiment’s workload. These simulations provide an extremely valuable tool for testing algorithms and models before deployment, gaining insights about the operation of the experiment, and providing vital information for the final measurement. These simulations however usually take a very long time to produce. I myself spent quite a bit of time simulating particle tracks that I could test a tracking algorithm on. The time-intensive nature of said simulations is due to both the amount of statistics necessary to generate, usually upwards of a billion events, and the fact that every single event has to be processed independently, step-by-step. Geant is the current main framework for simulating particle distributions and is immensely powerful. While the code itself is not slow, the degree of complexity in simulating billions of physical interactions in an accurate manner adds up. GANs, because they can learn to generate data with the same distributions and statistics as input samples, offer an attractive possibility to simulate these particle distributions in a way that is multiple orders of magnitude faster than Geant. This could save thousands upon thousands of CPU hours, which is an incredibly valuable resource.

|

|---|

| Comparison of Monte Carlo particle distributions generated with Geant4 versus a GAN model. Source |

Summary

The use cases I’ve described here just barely scratch the surface. Beyond all the numerous additional variations of the above categories, machine learning models can be used for anomaly detection for new physics, decorrelation methods, density estimation, track reconstruction, uncertainty quantification, data quality control and management, and many more. All in all, machine learning offers a wealth of potential improvement to a wide variety of use cases throughout particle physics. What was rare ten or so years ago is now becoming more common place and even vital. If an experimental result didn’t use machine learning methods in it’s final analysis, then it almost certainly used it somewhere upstream in an indirect way. As the years go by machine learning will makes it’s way into more and more applications, and I’ll be very interested to see what the landscape looks like ten years from now.

Sources:

- Living Review of Machine Learning for Particle Physics - GitHub repository containing links to many papers on the subject

- Introduction to Machine Learning in High-Energy Physics by R. Haake

- Machine Learning at LHCb by N. Kazeev

- Machine Learning in Atalas by S. Thais

- Machine Learning in Particle Physics by M. Williams

If you have anything interesting to add, please do not hesitate to contact me. I may return to this article at some point and expand it further like it deserves.